Porting to OS/2

from the November 1987 issue of PC Tech Journal magazine

An inside look reveals how one company rapidly converted a complex data manager from DOS to the OS/2 environment.

by Steven Armbrust

When Microrim, Inc., became a beta site for IBM’s new Operating System/2 (OS/2) in late 1986, Microrim chairman and founder Wayne Erickson knew immediately what he and his staff had to do. Not only did they have to convert R:BASE System V, Microrim’s largest and most complex database manager, to run under OS/2, but the job had to be done in time to demonstrate a working product when IBM officially announced OS/2. At the time, no one knew how soon the announcement would occur (it came just six months later).

Microrim—located in the same Redmond, Washington, neighborhood as OS/2’s developer, Microsoft—is a forerunner in converting to OS/2. The company internally committed to the OS/2 conversion of R:BASE System V in late 1986 and completed it in time to demoastrate the product at IBM’s formal announcement of OS/2 on April 2 of this year in Miami.

“We knew the job would be big, because our program is big,” Erickson said. “But with all the enhancements we wanted to make to our product, and because of the endorsements of IBM and Microsoft, we felt we couldn’t ignore OS/2.”

Microrim is counting on OS/2 to be a big boon in the constant battles die company must wage with competitors, most notably Ashton-Tate of dBASE fame, to add new features and otherwise improve its products. For R:BASE System V, which already strains at the 640KB memory bounds that are available under DOS, OS/2’s 16MB of memory will open the door to new features. It will also improve system performance by eliminating the need for cumbersome overlays used to squeeze numerous program elements into the overflowing 640KB memory bag. As it is now, heavy use of overlays as required by R:BASE uiider DOS diminishes the product’s performance even on an AT-class computer.

Microrim approached the OS/2 conversion systematically and found it relatively uncomplicated, said company managers, largely because R:Base System V (like all Microrim products) is modularly designed, thus nullifying the need for complex and interconnecting adjustments during conversions. The converted R:BASE System V is capable of running under OS/2 and using OS/2’s expanded memory and some multitasking capabilities with other OS/2 applications; however, it does not yet fully tap all OS/2 features, such as multithreading and the operational doors that capability can open.

The converted R:Base System V is not yet on the market and prices are unavailable. Microrim plans to release the product when IBM releases OS/2; meanwhile. Microrim engineers are working to enhance it with features arising out of capabilities specific to OS/2. According to Microrim, R:Base System V will remain available in DOS for users who do not want to convert their operations to OS/2.

PLANNING THE CONVERSION

As Microrim managers sat down late in 1986 to plan for the OS/2 conversion they were faced with several questions. How could Microrim engineers, who were just learning OS/2 themselves, convert an application as large and complex as R:BASE System V to the new operating system? What was the best way to proceed to optimize company resources? Should Microrim create a family application (one that could run under both DOS and OS/2 but that could not take full advantage of new OS/2 features such as extended memory and multitasking) or a separate application for OS/2 that would allow R;BASE System V to take advantage of the full extended OS/2 features? How should they proceed with the inevitable language conversion (from FORTRAN to C), and should they rewrite the program by hand or use an automatic language translator? Finally, how could Microrim accomplish the conversion in time to meet the fast-approaching (but still unknow’n) IBM deadline?

The company. From all observations. Microrim and its R:BASE System V product were ahead of the conversion game from the start. First, Microrim had previous experience converting products to new operating systems. Second, the modular nature of R:BASE System V allowed for the conversion to be done by making some rather simple, segregated changes as opposed to making complex and extensive modifications.

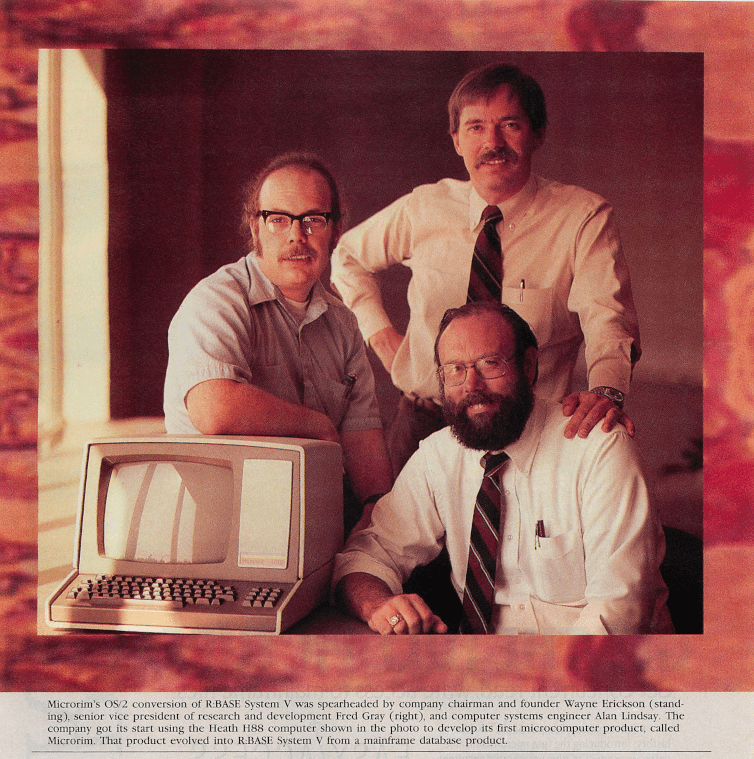

Microrim was formed by Erickson in November 1981 to develop a microcomputer version of a mainframe database product called RIM (for relational information management) that he had created for NASA in 1978 to validate relational database technology. RIM was subsequently made available on 22 different mainframes, including those made by Control Data, Cray, Burroughs, DEC, and Prime. Microrim’s first product—the minicomputer version of RIM—was named for the company and released for use on CP/M-based machines in July 1982.

Later that year, the company did two ports—one to IBM’s DOS and one to Convergent Technologies’ CTOS. In October 1983, Microrim did a major revision of the product and renamed it R:BASE 4000, followed by another major upgrade called R:Base 5000 in April 1985 (reviewed in “A Data Manager with Kernel Code Generation,” Steven Armbrust and Ted Forgeron, September 1985, p. 82) and, ultimately, the release of the current product, R:BASE System V, in July 1986. In the six years since it was founded. Microrim has grown from a company with seven people to one with 135 employees.

Decisions. Although Microrim management remains committecj in the long term to enhancing R:BASE System V so that it can eventually use all applicable OS/2 features, time constraints forced the company to take a conservative approach in the beginning. Instead of redesigning the product to add the new operating-system-supported features, Microrim initially decided to make a direct port of tlie existing product in order to meet the tight schedule. With this port, r.base System V immediately takes advantage of OS/2’s larger memory space and ability to run concurrently with other OS/2 applications; however, it still needs flirther enhancements to take advantage of all the other features of OS/2.

Further, Microrim decided to create a separate application for OS/2 rather than a family application; whereas a family application would have the advantage of running under both OS/2 and DOS (thus minimizing the number of different packages Microrim would have to stock, support, and maintain), it would be limited to using only OS/2 features that have counterparts under DOS. Despite the advantages of a family application, however, Microrim managers decided without hesitation to develop separate applications for OS/2 and DOS. Their goal was to create a product that does not limit OS/2 users to those features of OS/2 that are also available under DOS.

“We did not want to be unnecessarily constrained by the memory limitations of DOS, so we chose to go with two versions of the product, one for DOS and one for OS/2,” explained Alan Lindsay, Microrim’s computer systems engineer who performed the OS/2 conversion. Lindsay expects other developers of large applications to make the same choice, leaving the family-application approach primarily for utility programs, such as compilers, that do not require internal multitasking or large memory space.

Finally, Microrim needed a strong configuration control system. (For a review of six such products, see “Tracking Code Modules,” Jim Vallino, September 1987, p. 50.) This would allow its staff both to upgrade the company’s products individually and to maintain a common database for making generic changes simultaneously to all products. Configuration control is important because Microrim intends to sustain updated DOS and OS/2 versions of all its products, including Clout (a user query interface) and Program Interface (a programming tool).

After examining several commercial configuration control systems, however, Microrim decided to build its own system in R:BASE System V because it could not find one on the market to meet its specific needs.

The strategy. Microrim approached the OS/2 conversion of R:BASE System V in two stages. The first was a language conversion (most of R:BASE System V was written in FORTRAN, but in order to use OS/2 as it currently exists, the program had to be translated to C). The second phase was the actual conversion from DOS to OS/2.

THE SWITCH TO C

When R:BASE was developed, FORTRAN was the most portable language available and Microrim engineers knew it well—largely because R:BASE’s RIM ancestor was written in FORTRAN . Thus, the original R:BASE was in FORTRAN, but enhancements to later R:BASE versions were written in C. Going into the OS/2 conversion, R:BASE System V still contained 70 to 75 percent FORTRAN code, 10 to 20 percent C code, and the remainder was in assembly language.

No FORTRAN compilers are yet available for OS/2, so Microrim had to convert R:BASE before it could start the OS/2 conversion. Such a language conversion had been on the minds of Microrim developers for some time, but they were reluctant to undertake this major project for its own sake. As Erickson explained, “We feared that the entire staff would spend two years on a conversion and the product would do nothing different from the current product.” Nonetheless, Microrim engineers knew the language switch was inevitable—with or without OS/2—in order to keep R:Base System V competitive in the marketplace, so the company started the wheels for C conversion in motion last fall. It accelerated the conversion effort a few months later when OS/2 became a reality.

The conversion to C, including hand-tweaking, required four to five people over a period of three months. To save time. Microrim engineers used Rapidtech Systems, Inc.’s FORTRix-C, a language translator that reads source code in one programming language and produces source code in another language as output. Although the code produced by mechanical translation is not as efficient as code written by hand, the conversion package can produce an initial draft in the target language in a much shorter time. Engineer Lindsay explained that even when the translator’s output required further refining by customized conversion routines or hand-tweaking, using a translator significantly reduced the time and effort of producing a finished program in the target language.

A certain amount of post-processing of the translator output was inevitable because FORTRIX-C, as a general-purpose conversion program, could not be expected to meet all of the specific requirements of a program as complicated as R:BASE System V. For example, FORTRIX-C converts a FORTRAN COMMON block into a series of pointers to an array and generates code to initialize these pointers at every entry to a function. Microrim engineers therefore had to write their own routines to convert COMMON blocks to C structures that require no address manipulation at runtime.

In addition, FORTRIX-C automatically generates all integers as long integers in C, but Microrim wanted them to be short integers; therefore, this had to be done manually. Finally, because FORTRIX-produced code is less efficient than handwritten code. Microrim engineers reviewed the FORTRIX-generated code when time allowed and manually us statements, reducing the size of the source code by approximately one-half.

The engineers confronted an interesting problem during the language conversion; when a math coprocessor was not present, floating-point operations were much slower in C than in FORTRAN. This was because Microsoft’s FORTRAN and C compilers use two kinds of floating-point libraries. The standard library uses a math coprocessor if it is present or emulates it in software if it is not. The other, called the Alt Math library, always performs floating-point calculations in software. The efficiency of emulations in the two libraries is not always equal.

In version 3.3 of Microsoft FORTRAN, which was used to compile the FORTRAN code of R:BASE System V, the emulating routines in both libraries performed equally as fast. When the converted code was compiled with the Microsoft C 4.0 compiler, however, the emulation routines in the standard library were considerably slower than those in the Alt Math library. The Microsoft FORTRAN 4.0 compiler experienced the same problem with emulated floating-point routines.

Microrim considered using the Alt Math routines to achieve increased floating-point execution efficiency on systems without a math coprocessor (still the majority of PC systems). But this had two disadvantages. First, software routines in the Alt Math library gained execution efficiency at the expense of numeric accuracy and error checking. Second, the performance of an Alt Math product could be improved by adding a coprocessor.

In a database manager, floatingpoint efficiency is significant only if real-number data exist in the database; otherwise, manipulating data files is not a compute-intensive activity, and integer arithmetic is adequate for whatever computations are required. Therefore, Microrim engineers decided to accept the slower execution efficiency of the standard math library. In return, users have increased accuracy. For applications requiring upgraded efficiency, users can add a math coprocessor.

“The [language] conversion encouraged our development staff because they found they could take advantage of the C environment and decrease the code size of the product. Plus, they had a chance to clean up routines written several years ago and make the code tidier,” Microrim chairman Erickson said.

Microrim’s work was far from finished once the C conversion was complete, however. It still had to convert the C code to run under OS/2.

ONE-MAN JOB

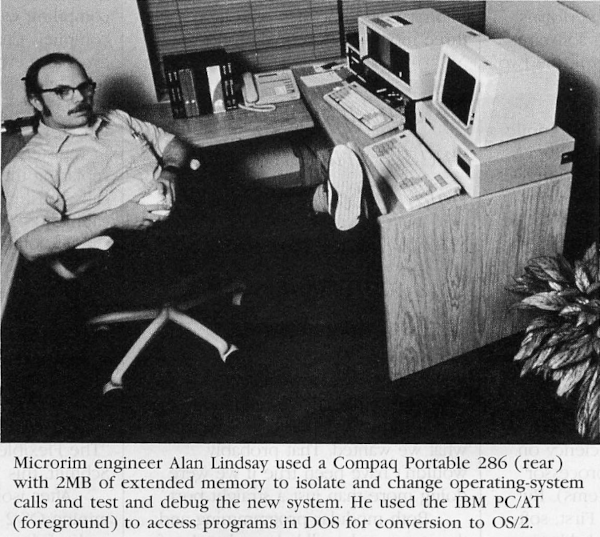

The OS/2 conversion was less involved than it might have been because Microrim earlier had decided to limit its near-term efforts to producing a functionally equivalent OS/2 version of R:BASE System V without adding all the bells and whistles. Lindsay took on the job himself, using a Compaq Portable 286 computer with 2MB of extended memory. The one-man operation took three months. “In terms of effort, it was really only about half of a conversion,” he said. “There weren’t any big surprises; we were able to do exactly what we wanted. That probably wouldn’t have been true if we were doing more than just a straight port.”

Both modular programming and the structured, well-balanced code of R:BASE System V substantially expedited the OS/2 conversion. Erickson explained, “We’ve always tried to keep our machine- and operating-system- dependent code clearly isolated, so the number of routines we had to change for OS/2 was considerably smaller than it could have been.”

Earlier conversions of Microrim products from different operating systems compelled company engineers long ago to isolate all operating-system-specific operations into a small set of procedures that other routines call whenever they need operating-system services. This set of procedures was placed into a library. Instead of making DOS calls directly, the rest of the routines in R:BASE System V called the routines in this library. As a result, the task of isolating DOS calls is easier, and fewer system-specific modules need to be rewritten.

Of approximately 2,500 total routines making up R:Base System V, only 25 to 50 of them contained DOS calls that needed to be converted. Consequently, only about two percent of approximately 90,000 total lines of source code needed to be changed. Procedures that did not issue operating-system calls were able to function under OS/2 without change because none of them breaks rules of protected-mode operation, such as performing arithmetic on segment registers or attempting to access memory outside assigned memory space.

Any operating system functions handled by calls to standard C library routines were, for the most part, automatically taken care of simply by recompiling with the OS/2 version of the compiler. Changes were required, however, in the operating-system calls issued by assembly language routines. The majority of effort was spent isolating all DOS-style calls (placing values in registers and issuing an INT 21) and replacing them with equivalent OS/2 calls (pushing values on the stack and calling OS/2 procedures).

In some cases, the conversion could be applied at a higher level. Because of the higher-level syntax of the OS/2 applications program interface (API)—ffie rules for calling up OS/2 routines—some calls to assembly language routines implementing customized system interfaces were replaced with direct calls to OS/2 funaiohs. (See “The Flexible Interface,” David A. Schmitt, this issue, p. 110.)

After isolating DOS calls and determining OS/2 equivalents, Lindsay tested each of the new system calls with a small test program. By taking this approach, Lindsay could monitor system operation and determine any operating quirks, performance problems, or bugs. He was able to determine immediately whether he would need to redesign parts of the application because of differences between DOS and OS/2.

In at least one instance, Lindsay had to make some modifications. Applications that formerly wrote to DOS video memory easily wrote to the OS/2 logical video buffer, but applications that send characters to the screen one at a time experienced a significant slowdown. To improve performance, Lindsay reprogrammed the R:Base video procedures to write a string of characters to the logical video buffer first, then to update the screen.

The extent of IBM and Microsoft contributions to the R:BASE System V conversion effort is unclear. “We had what we needed, and we got help when we needed it,” Lindsay said, but he would not elaborate because of a confidentiality agreement that Microrim signed prior to the conversion. Neither would Lindsay describe the documentation he worked from, although it is safe to assume that the material was similar to the OS/2 Software Development Kit now available commercially.

BETTER WITH OS/2

Because the conversion went smoothly, Microrim completed its prototype OS/2 version of R:Base System V in time for the introduction of IBM’s OS/2 on April 2 in Miami. The conversion was essentially a direct port of the DOS version, but it automatically takes advantage of a couple of OS/2 features.

First, the ported program is not restriaed to DOS’s 640KB memory limitation. Instead of being heavily overlaid as the DOS version is, the entire program (approximately 680KB worth) is loaded into memory at once. This improves the performance of the product, and it also eliminates the development burden of having to plan an overlay structure to optimize performance.

In addition, R£ase System V and other OS/2 applications can be multi-tasked or a user can invoke two copies of R:BASE simultaneously to obtain multitasking features not built into the program. For example, a user can start up one copy of the program to print out a report and start another one to enter records into the database. Because OS/2 shares code segments, the memory space required by each subsequent invocation of a program is significantly less than the first. Also, because DOS’s networking features are carried over to OS/2, R:Base System V’s built-in networking capabilities enable multiple invocations of the program, as well as multiple users, to update the same database without fear of corruption.

Microrim did not find that the OS/2 version of R:Base System V runs any slower than the DOS version. Certainly, OS/2, as a multitasking operating system, has more overhead and could, in general, be expected to run slower than a single-tasking application such as DOS. However, because Microrim was able to remove the overlays required under DOS for R:BASE System V, the company actually improved the performance of the OS/2 version.

Instead of focusing on raw speed for isolated functions (i.e., sorting). Microrim believes that users should look at total throughput over time of combined functions (sorting, printing, etc.) to determine whether an OS/2 version of an application is superior or inferior to a DOS version. “It’s not how long a sort takes, but how much I can get done in an hour that’s important,” Fred Gray, Microrim’s senior vice president of research and development, said. The multitasking features of OS/2 give database users the ability to get more done per hour.

Microrim managers remain confident that the OS/2 conversion was worthwhile and has put them in an ideal position in the marketplace. If IBM releases OS/2 immediately, Microrim could release the ported R:Base within days. Meanwhile, they have a team of developers enhancing the product with OS/2-specific features.

The upcoming Presentation Manager, being developed by IBM and Microsoft for use with OS/2, presents another opportunity to Microrim. Although sophisticated database users might not be helped much by a graphical user interface, such as the Presentation Manager, Microrim understands that effective use of graphics can help novices pick up database concepts more easily. In addition, the ability to build graphically oriented database applications could help sophisticated users build better applications for novices to use. Because the release date of the Presentation Manager is uncertain, Microrim has not made firm plans about which Presentation Manager features to put in R:Base System V.

Even in their enthusiasm to develop an OS/2-only version of R:Base System V, Microrim officials have not deserted their DOS customers. The company already supports its products on both CTOS and DOS, and OS/2 adds another entire operating system to the list. In addition to converting R:BASE System V, Microrim plans to update all of its products to take advantage of the new OS/2 features. All other Microrim products, except Clout, already have been converted from FORTRAN to C. Because they use a common set of library routines to perform system operations, converting other products to OS/2 should go even more smoothly tlian R:BASE System V.

Microrim was in the right position at the right time to do a quick conversion to OS/2. The company’s database management products are well suited to quick conversion because they are not graphically based and do not break any operating-system interface rules, such as writing to unallocated memory. More importantly. Microrim was experienced in converting to other operating systems, so it knew the importance of writing modular, well-behaved code.

Lindsay cautioned against expecting to convert all DOS calls to OS/2 and have them work right away. He stressed use of modular code and recommended making poorly structured DOS programs modular first, isolating operating-system calls to a few procedures. When restructured code is working correctly under DOS, operating-specific-routines can tlien be recoded under OS/2 and tested. By isolating operating system calls to just a few procedures, OS/2 conversion involves changing only a small set of procedures, not searching through every line of source code. “Even if you don’t have modular, well-behaved code before you start converting, you will when you finish,” Lindsay concluded.

Microrim

3925 159th Avenue, NE Redmond, WA 98052-9722 2061885-2000

R:BASE System V (DOS version): $700

Steven Armbrust is a freelance technical writer who has been a contributing editor to PC Tech Journal for the past two years.